Innovations Magazine

We are excited to share this collaborative article that we wrote for Innovation Magazine’s Spring 2025 Issue; What Does Breakthrough Design Look Like?

Biomimicry’s Life’s Principles and Industrial Design

Biomimicry is an exciting branch of science, a sustainability ethos, and an inspiring new design movement. (Bios is Greek for life, and mimesis means “to imitate.”) Nature has had 3.8 billion years of R&D to create the successful biological solutions we see all around us today. Unfortunately, since the start of the Industrial Revolution, humans have been making their products in a way that depletes Earth’s resources. Biomimicry can teach us how to give back and turn our focus to regeneration.

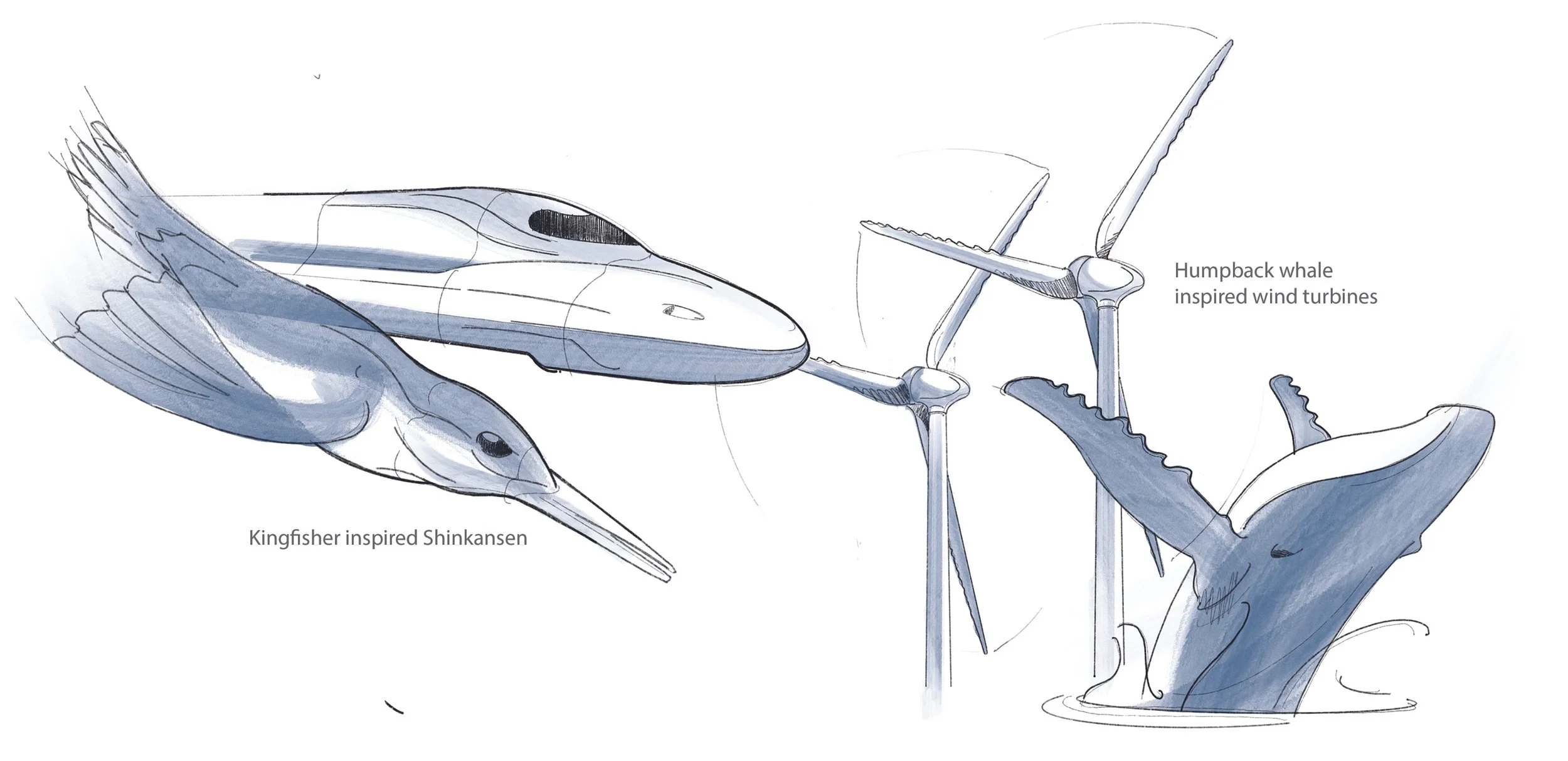

There’s a well-known biomimicry story about an engineer who noticed bumps along the leading edge of humpback whales’ flippers on a sculpture. This seemed strange, as he assumed the leading edge should be smooth. Curious, he tested small bumps on his wind turbine project and discovered the blade’s efficiency increased by about 30 percent, significantly reducing drag—similar, perhaps, to a serrated knife blade.

Another great example is Japan’s Shinkansen. The bullet-shaped train’s nose initially created a sonic boom when exiting tunnels. The engineers drew inspiration from a kingfisher’s elongated beak and head, which allows the bird to dive cleanly into water, barely making a splash. Redesigning the train’s nose allowed it to travel 10 percent faster and eliminated the boom.

We can study nature’s genius designs and emulate them on three levels. The first level is mimicking form, which is the simplest to do, but in many cases remains about outer looks. The second level is mimicking the process, which requires a more in-depth study and understanding of the inner function. The third is the systems level, which is the hardest to do. But this is where the magic is—it is where we can achieve circularity in the product development cycle. How? By interconnecting companies or technologies to take each other’s “waste” or by-product and use it as “nutrient” material to create new products.

Sketches by Treasure Hinds

Life’s Principles and Industrial Design

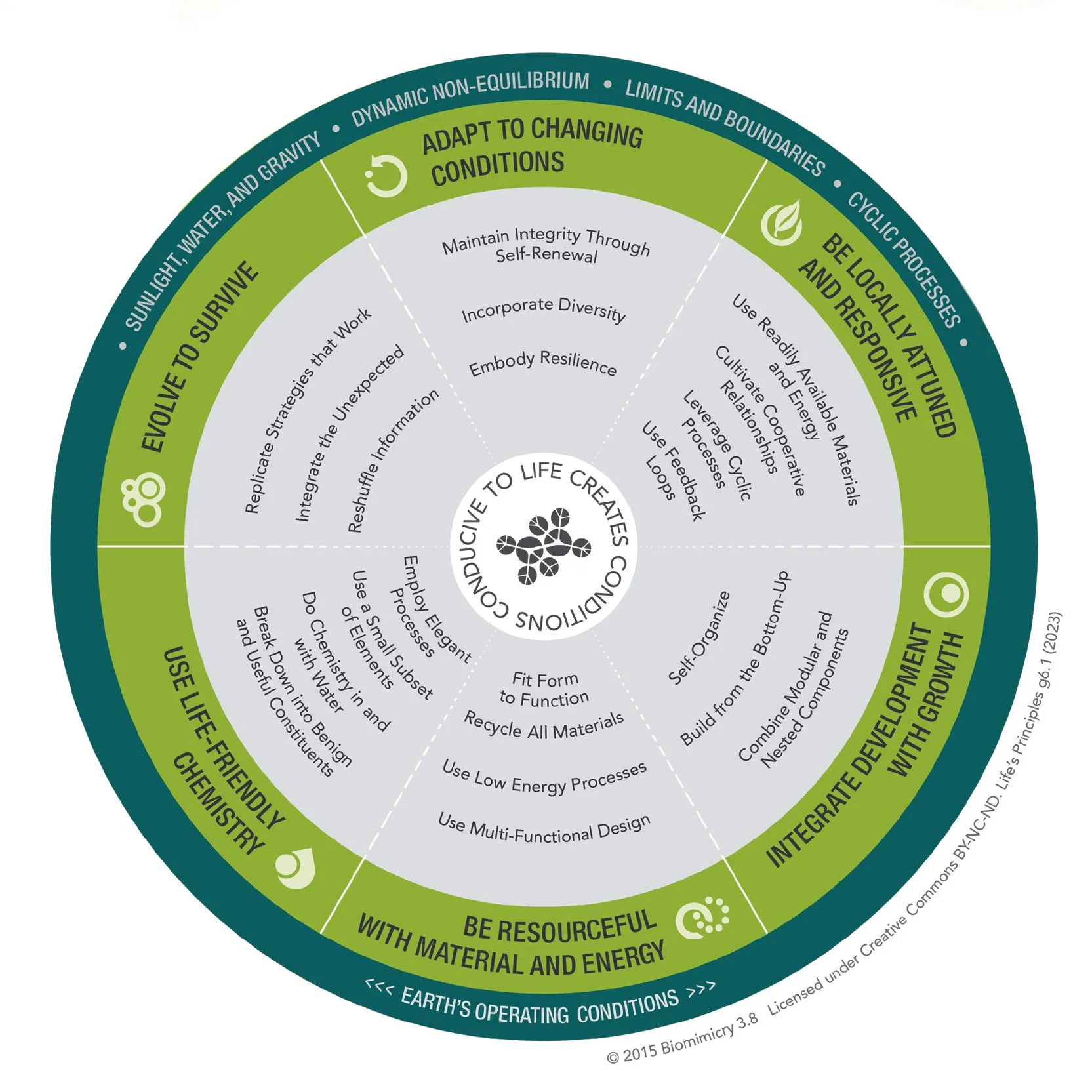

Biomimicry introduced us to Life’s Principles (LPs), the term for a collection of guidelines created by scientists and based on nature’s strategies. These principles are repeating patterns observed in nature that provide lessons for sustainability and success. Plants and animals “manufacture” materials on their bodies, such as a beetle making chitin. Still, when nature produces materials, they are not heated to high temperatures, nor beaten under lots of pressure, nor treated with harmful chemicals. Human’s heat-beat-treat manufacturing methods are a different story. We damage the planet by continuing to mine for nonrenewable energy sources and polluting the natural environment with toxic chemicals.

By contrast, Life’s Principles help us understand “what works, what is appropriate, and what lasts here on Earth,” as biomimicry pioneer Janine Benyus puts it. Some of those principles include:

· “Be locally attuned and responsive.” Fit into and integrate with the surrounding environment.

· “Be resourceful with material and energy.” Optimize the use of resources and take advantage of opportunities.

· “Integrate development with growth.” Balance investments to move toward an enriched system.

· “Fit form to function.” Design for shape or pattern based on need or purpose.

In an ideal setting, you have a biologist at the design table to share nature’s genius but even without one, you can start using biomimicry’s LPs today. The key is to weave the LPs into the design thinking process. This means understanding, translating, and applying the LPs as any other organizing principle you use in your design approach. Designers can use LPs to define objectives and brainstorm, helping to develop new, life-centered solutions that would not otherwise surface. This particularly matters in design education because this generation of design students will have to hit the ground running as compassionate climate designers the day they graduate.

LP and ID, Step by Step

The first step in building biomimicry into design is integrating the LPs into scoping. In any design challenge, finding and understanding (identifying) the function should be at the center. From there, designers define the context around this function by asking the 5 W questions (who, what, where, when, why). Once those are identified—perhaps on paper and large wall boards—it’s time to integrate LPs as organizing principles that we commit to, right from the start.

Some may want to find inspiration at this point. We could argue that it should be a requirement for all designers to go for a walk in nature or watch a nature documentary. Sketching and ideating outdoors, in a park or garden, using IDEO’s rules of brainstorming (no judging, no “bad” ideas, etc.) is an excellent way to prepare. Look at ways to “translate” LPs into your work. LPs can be interpreted in more than one way (abstract versus literal), but the most crucial thing is to understand them first. Brainstorming sessions can be the perfect time to apply these LPs (nature’s patterns) to design ideas. Asking how a design can be locally attuned and responsive will spark plenty of questions: What are the resources, technologies, and cycles in this local place? What’s available, what’s needed, and how can we connect the two?

Generative AI can be of assistance here. Inviting it to be our creative collaborator and asking for help in developing new conceptual ideas based on LPs might be a game changer in our process. Generative AI’s strength is in language, so our prompts are essential; one must give AI a “translation” of each LP before asking it to generate ideas. Designers should also be concerned about using this new aid wisely and responsibly, especially regarding sustainability, as AI notoriously consumes a great deal of energy. Perhaps there is an opportunity to apply LPs to help solve even this challenge.

Biomimicry 3.8 Life’s Principles 2023

Life’s Principles (LPs) in Practice

To help illustrate life-centered design in action, here are a few examples we have observed of LPs implemented in contemporary product design:

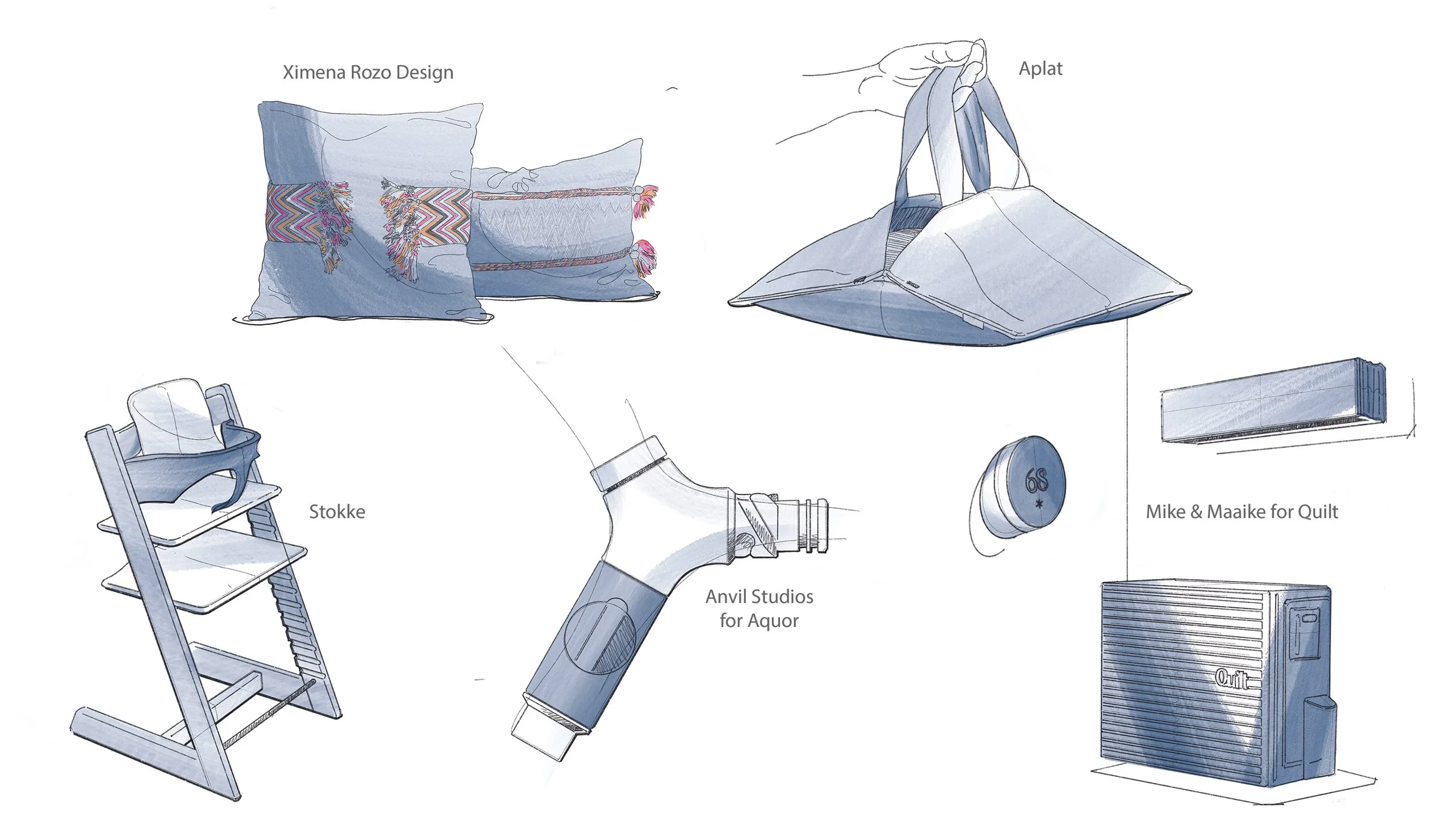

1. Ximena Rozo’s indigenous heritage design objects

LP found: Be resourceful with material and energy.

How it shows up: Uses low-energy, traditional fabrication methods like weaving, plant-based coloring, and low-carbon-footprint materials (wool, alpaca).

LP found: Be locally attuned and responsive.

How it shows up: Uses traditional indigenous methods, creates win-win interactions with artisans, fosters economies, ensures a deep connection to place and tradition.

2. Aplat’s zero-waste design approach

LP found: Be resourceful with material and energy.

How it shows up: Uses certified-organic materials with no extra plastic or elastic added, ensures long-term use even through many washings. Upcycles excess material.

LP found: Be locally attuned and responsive.

How it shows up: Uses locally sourced materials, makes products across the street, aligning with the eco-conscious consumer culture of the place. Connects friends and neighbors over food and wine.

3. Stokke’s enduring high-chair design

LP found: Integrate development with growth.

How it shows up: Has the ability to change and grow. It uses horizontal grooves and simple adjustable panels to evolve as the child grows from baby to toddler, school age, and beyond.

LP found: Fit form to function.

How it shows up: Uses a triangular V-shaped frame holding two flat platforms. The minimal shape with basic horizontal planes creates a strong structure that simply elevates the child to the correct height of any dining table.

4. Anvil Studios’ nature-inspired design for Aquor handles

LP found: Fit form to function.

How it shows up: Mimics the tree branch angle for efficient water flow. (Tree branches dividing at 45-60° are experts at delivering water efficiently.)

LP found: Be resourceful with material and energy.

How it shows up: Utilizes durable materials for longevity. Overmold material is only applied where it is functionally needed.

5. Mike & Maaike’s sustainable design for Quilt home climate system

LP found: Be locally attuned and responsive.

How it shows up: Senses (detects) room occupancy, saving energy by not heating or cooling empty rooms. Offers individualized room temperature control.

LP found: Integrate development with growth.

How it shows up: Allows components (four parts) to be added or removed, depending on the home’s needs, easily fitting into new or remodeled places.

Sketches by Treasure Hinds

Next Steps

Traditionally, sustainability focuses on small-scale productions, but even designers of mass-produced products can shift their thinking and move away from human-centered to life-centered design thinking methods. By implementing biomimicry’s Life’s Principles into our process, and by speaking up, asking good questions, and demanding better solutions, designers can become agents of change within our creative communities. We can implement the LPs throughout the design development process, incorporating them from the start as our true north, or organizing principle, and framing the project’s objectives. The LPs can also benefit the brainstorming phase if we accept them as new tools in the toolbox. Generative AI, acting as our creative collaborator, combined with “translated” LPs can further our ideation. LPs are also excellent for evaluating existing products.

As our blue planet faces unprecedented temperatures, wildfires, floods, and droughts, we desperately need a paradigm shift, a quick mindset change, and a new way of designing. Life's Principles are biomimicry’s most crucial message and incredible gift for us designers. They provide a newfound hope that we can design with ethos, intelligence, respect, and love for our planet and future because change is needed.