How to trap prey without teeth or claws

Aquaplaning in pitcher plants

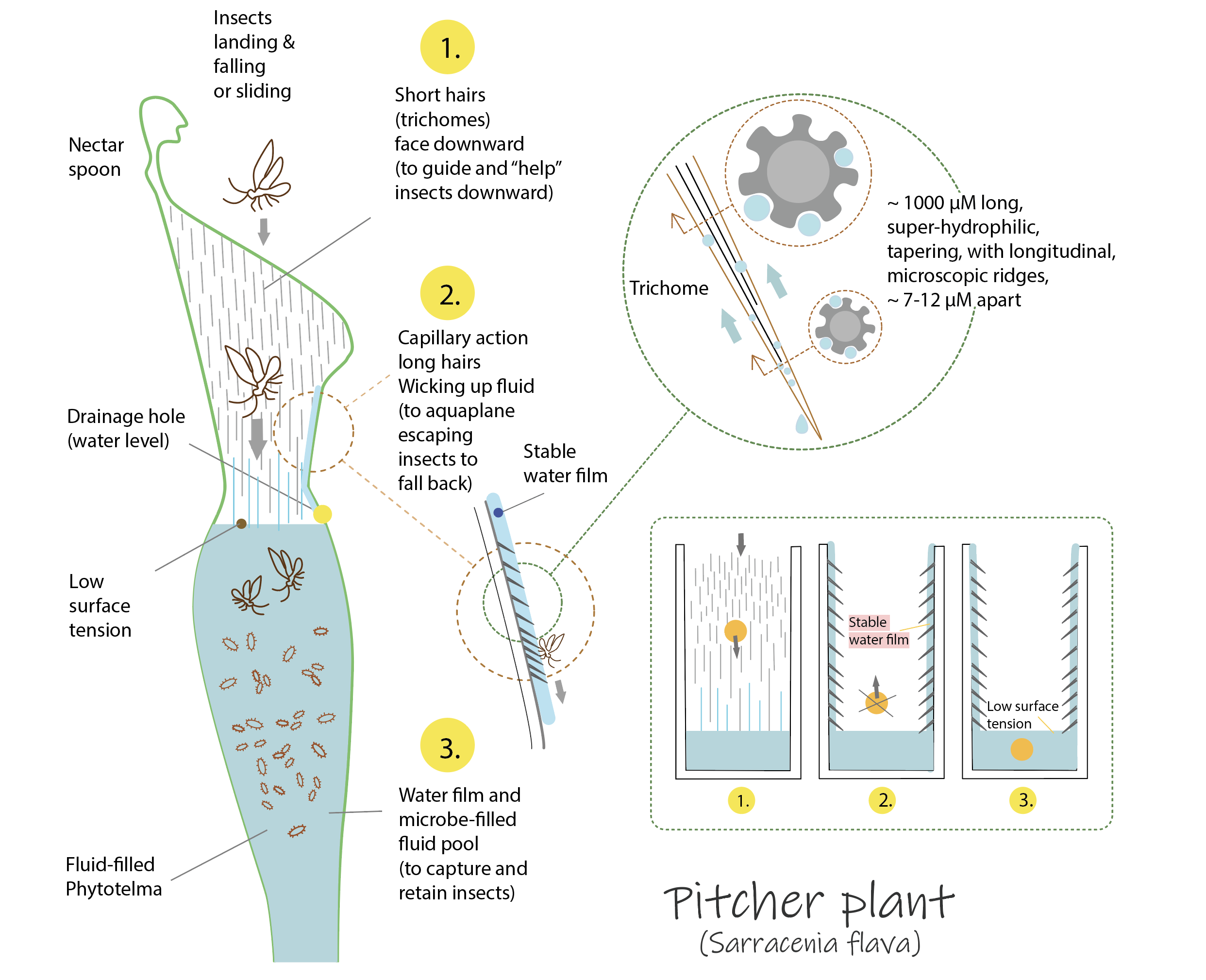

In nutrient-limited wetlands, where soil lacks essential resources like nitrogen, some plants have evolved an unexpected strategy for survival: carnivory. Instead of relying solely on the ground for nutrients, these plants obtain what they need by trapping and digesting insects. This unusual adaptation has given rise to a group of plants that lure, capture, and break down prey using structure, chemistry, and gravity, even without teeth, claws, or movement. Meet the yellow pitcher plant (Sarracenia), a carnivorous plant that has evolved a surprisingly sophisticated way to trap insects using slippery surfaces and carefully engineered textures.

The pitcher plant learned to trap prey by making insects slide

The yellow pitcher plant lures insect prey to its elongated, tube-shaped leaves using a sweet nectar. This nectar is laced with an alkaloid poison called coniine, which intoxicates insects and reduces their ability to escape once they enter the trap. Drawn by the scent and sweetness, insects land on the rim and upper portion of the pitcher. This upper zone is smooth, waxy, and extremely slippery. Once inside, insects lose their footing and begin to slide downward; an effect often described as aquaplaning.

What is the strategy or mechanism we can learn from?

The pitcher plant’s trapping mechanism is entirely passive. After entering the tube, insects encounter a layer of ultra-fine, downward-pointing hairs that guide them deeper into the pitcher. These hairs act as a one-way system, allowing movement downward while preventing insects from climbing back up. At the base of the tube, insects collect in a pool of digestive enzymes. The smooth, waxy inner walls prevent escape, while the intoxicating effect of coniine further hampers coordination. Over time, the insects are broken down, and specialized cells at the base of the pitcher absorb the nitrogen-rich nutrients released during digestion. No movement is required. No force is applied. The entire system relies on geometry, surface texture, chemistry, and gravity.

Illustration by Agota Jonas

The lesson we can learn here

What works so effectively in the pitcher plant is the combination of:

-Slippery, low-friction waxy surfaces

-Directional micro-textures in the form of downward-pointing hairs

-Funnel-like geometry

-Passive chemical assistance

-Gravity as the driving force

Together, these elements create a one-way system that guides insects inward and prevents escape, without mechanical parts or energy input.

Can we mimic this strategy?

Could we design materials or surfaces that guide movement using texture alone? Could architecture, products, or infrastructure take advantage of directional friction to move water, particles, or objects exactly where we want them to go?

The pitcher plant reminds us that some of the most effective designs rely not on force or complexity, but on the careful orchestration of material properties and form.

References

Christensen, N. (1976). The Role of Carnivory in Sarracenia flava L. with Regard to Specific Nutrient Deficiencies. Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society, 92 (4), 144-147.

Gayther L. Plummer, and John B. Kethley, "Foliar Absorption of Amino Acids, Peptides, and Other Nutrients by the Pitcher Plant, Sarracenia flava, "Botanical Gazette 125, no.4 (Dec., 1964): 245-260.