The beetle that learned to do headstands

Collect water vapor from the air

Collecting water from thin air is one of the functions we can observe in nature in many different places on this planet, even in deserts where annual precipitation is very low (less than 75 mm). This might be exactly the reason why the many species that survive in this harsh environment evolve to take water in whatever form they can. Some develop hairs that catch the tiniest water droplet, and some build surfaces that water droplets slide down on. Meet the Namib beetle (Onymacris unguicularis), a small, shiny-backed insect that evolved to collect water on its back, in the middle of the night, when the fog rolls in from the ocean.

The Namib beetle learned to do headstands to drink water

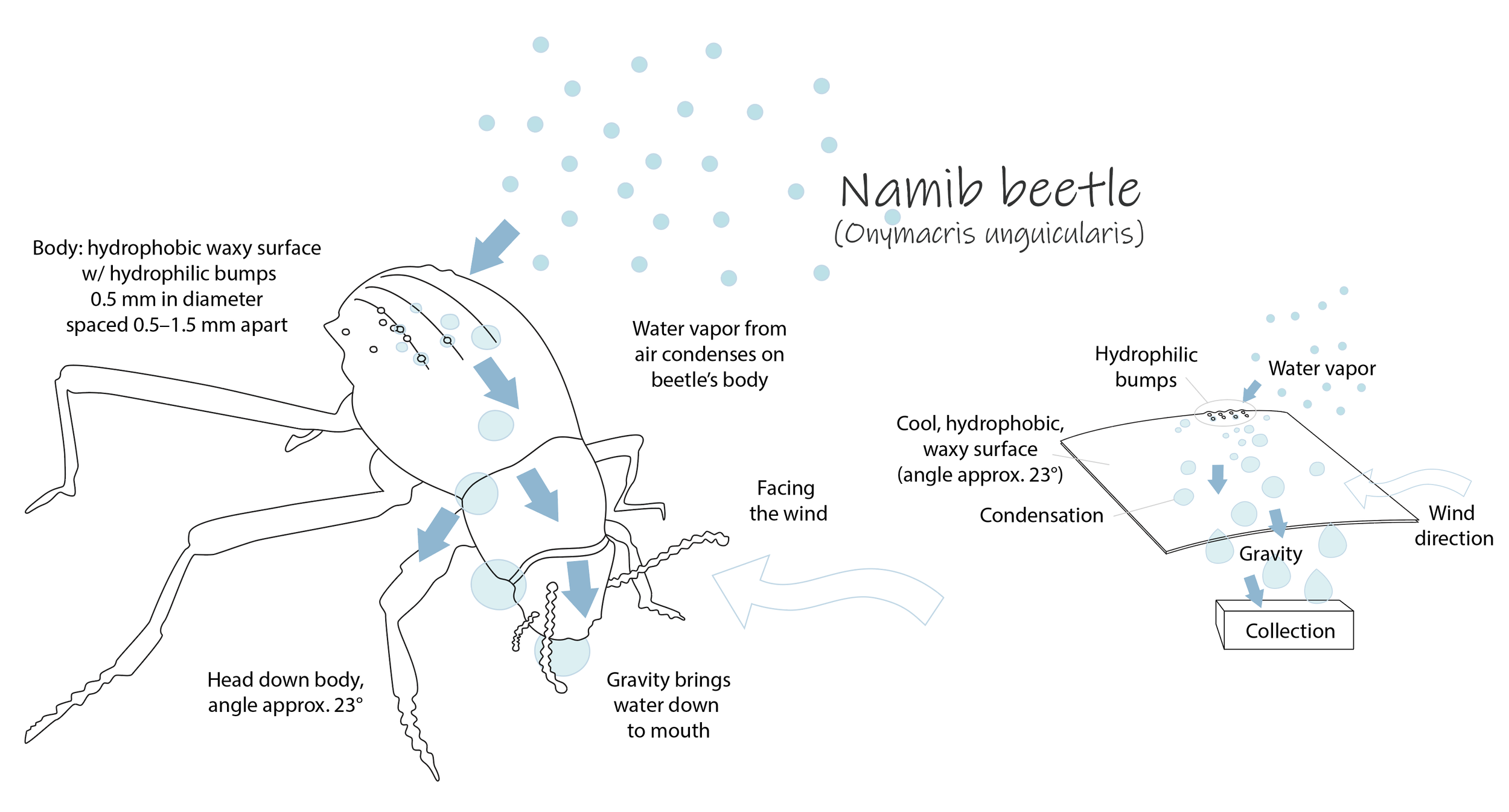

What is the strategy or mechanism that we could learn from? The Namib beetle harvests fog by emerging during nocturnal fogs, in the dry, arid Namib desert. It orients itself to face the wind in a unique, head-down body position at an angle of approximately 23°. It uses this body position, this unique behavior to catch water drops that condense on its cool body surface and collect into larger drops. These eventually run down toward its head, all the way to its mouth, where it drinks it.

The body position helps, but here is the secret: The beetle’s forewings have a combination of different textures: nanoscale hydrophilic round but elongated, smooth bumps that are about 0.5 mm in size in diameter, and spaced about 0.5–1.5 mm apart, and a nanoscale hydrophobic, waxy surface that surrounds the bumps. The hydrophilic bumps attract the water vapor and the hydrophobic waxy surface gathers it and helps the waterdrops roll down towards the head of the insect.

Illustration by Agota Jonas

The lesson we can learn here

What we see work here so beautifully is that a cool, tilted surface with hydrophobic grooves and hydrophilic bumps, (0.5 mm in diameter, and spaced 0.5–1.5 mm apart) condenses water vapor from air and channels it downward, simply taking advantage of gravity.

Can we mimic this strategy?

Could we add textured materials in our products or on buildings to condense water during cold nights? Should we rethink how we build our rooftops, and what new functions they could perform?

References

D. Gurera, B. Bhushan: Passive water harvesting by desert plants and animals: lessons from nature, Feb. 2020.

T. Nørgaard, M. Dacke: Fog-basking behaviour and water collection efficiency in Namib Desert Darkling beetles. Frontiers in zoology, 7. 2010.

J. Guadarrama-Cetina, A. Mongruel, M. G. Medici, E. Baquero, A. R. Parker, I. Milimouk-Melnytchuk, W. González-Viñas, D. Beysens: Dew condensation on desert beetle skin, The European Physical Journal E, Nov. 2014.